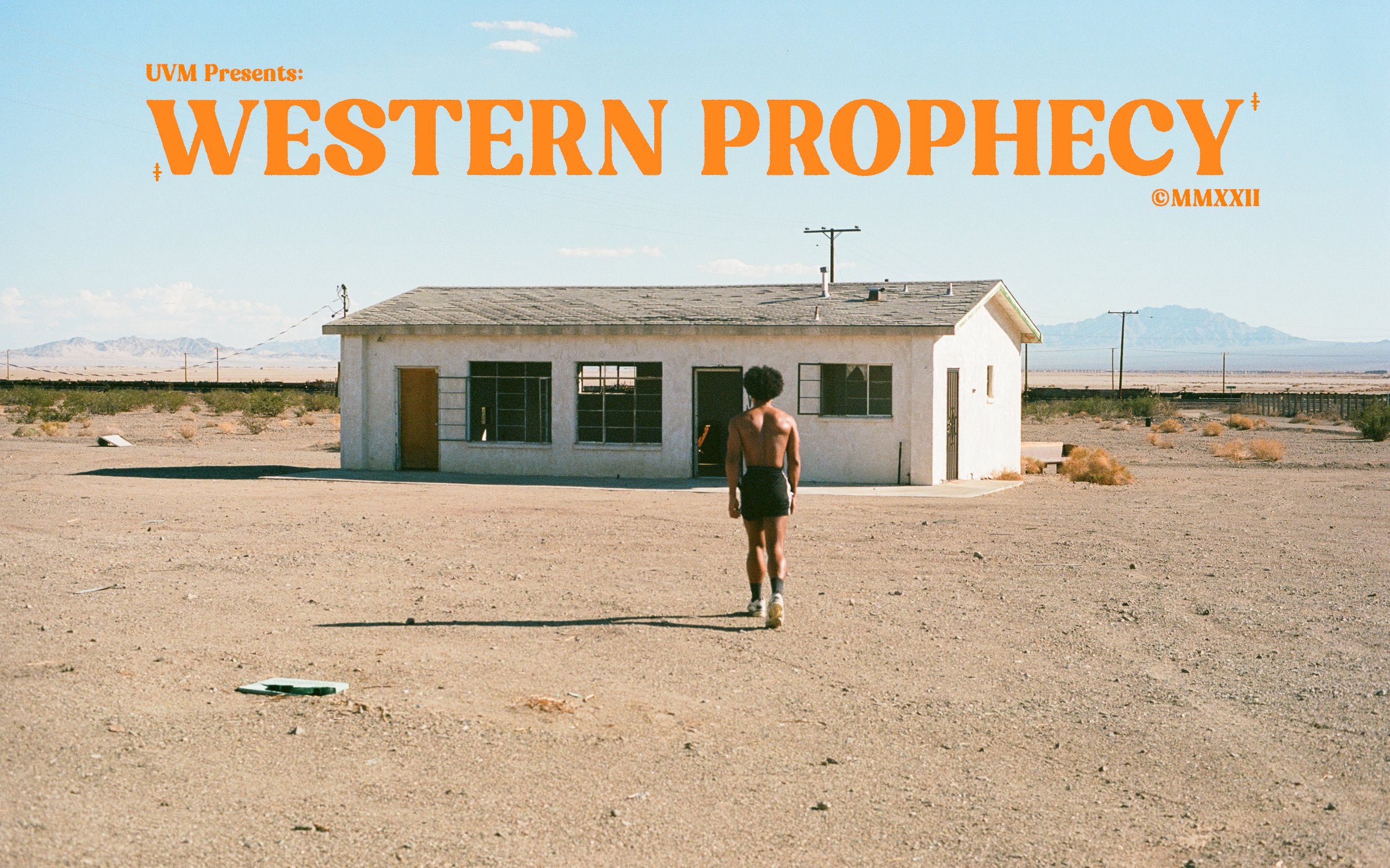

This is a digitization of my zine “Western Prophecy”, originally self published in 2022.

I’ve visited the Southwestern United States five times now. Each trip was a little different. Some I spent mostly in cities - Los Angeles for the most part, but San Francisco twice.

The more memorable trips were the ones when I drove. If you want to go between places on the ground out there, you have to drive. There isn’t even an option for a train between Las Vegas - America’s most popular city for tourists - and Los Angeles - the great megacity of the Southwest.

You have to drive.

But I love to drive.

Being a kid from the Great Lakes, this part of the world feels very different from what I know. When you get out of your air-conditioned car fresh from the lights of Las Vegas, the first thing that hits you is the heat. The second thing that hits you is the silence. When the warm wind stops blowing you can hear nothing. Just your footsteps on the scorched earth. You kick up dirt that settled long ago.

This dirt will settle once more and remain long after you’re gone.

All dirt tells a story. It was fallow dirt that forced thousands of farmers through this desert as they fled the midwest during the dustbowl. For them, California was a beacon of hope. Hope for new work, for a new life.

This was their Western Prophecy.

And they spent weeks, even months in Horse buggies, boxcars and beaten Model Ts trudging slowly across the desert trying to fulfill their prophecy.

In the heat and nothingness, many did not.

Back then there was one lonely road out here - US Route 66. This famed highway linked Chicago to Los Angeles and remained the main road until Interstate 40 was constructed to replace it in the early 1970s. Just before the Interstate came around Route 66 experienced a renaissance. American families enjoying the post-war economic boom were buying cars and a new type of tourism was taking shape: the road trip.

All along Route 66, enterprising people built motels, diners, gas stations and other amenities to serve these new types of travellers. Entire towns popped up for this purpose, and for a while business was good. The neon was glowing and the cash was flowing.

Western Prophecy.

And then it was gone. The traffic once steady now whisked along the Interstate, often only mile or two parallel. The towns built for the traffic emptied out, leaving only ghostly shells of what used to be.

Amboy, California is one of these towns.

The official sign outside Amboy says the town has a population of 20 people, but reports are that the towns population is actually only 4.

There are only a few buildings in Amboy, with one of the largest being Roy’s, a motel, gas station and diner complex fronting Route 66 in the centre of town. Like the other buildings in Amboy, Roy’s exists in a strange point somewhere between abandoned and revived, forbidden and accessible.

Forgotten by time but preserved in history.

The recently restored modernist Diner sits locked, awaiting potential conversion into a museum. The motel rooms - cutely arranged into small detached homes - sit disused but free to enter, with broken glass, peeling paint and only a sofa or chair inside. The gas station and attached cafe are open, staffed by a mother and her teenage daughter who commute here from an hour away.

As the mom cooks us a hot dog on the BBQ outside the front door - to hell with smoking laws - she tells us about the town.

Originally built in the 1930s by a man named Buster Burris, Roy’s and the rest of Amboy peaked with Route 66. Buster sold the entire town in 1995 to two investors who rented it out for film and photo shoots, but let it decline and decay and eventually lost it to foreclosure.

After this the town was repossessed by Busters widow Bessie, who sold the entire town to LA area restaurant magnate Albert Okura in 2005. Okura has led efforts to restore Roy’s, and wants to re-open the town as a functioning time capsule and destination for Route 66 tourists. In his own words, he sees restoring Amboy as part of his destiny.

This is his Western Prophecy.

Despite (or because) of the remoteness, the desert is littered with many strange artifacts of the limited human presence. We left Amboy headed south. Just before we Passed Twenty Nine Palms we stumbled across The End Of The World.

In these vast valleys distance and scale become stretched into abstraction. Freight trains hundreds of cars long become blocky snakes slithering across the desert floor. Lights from cars on the Interstate become fireflies rising into the dusk air.

Ten foot high letters become small alphabet blocks when viewed from a passing car, a hundred metres or so away. They contort to reveal their full scale, rising above the mountains as you walk closer. Overpowering them. Overpowering us.

Is this the end of the world?

At a glance it looks like the world has already ended in the town of Bombay Beach.

Perched on the eastern shore of the Salton Sea, 236 feet beneath sea level, this town was once a thriving resort community. It isn’t anymore.

About 120 years ago this sea didn’t exist. Although water had filled this basin at various times in the past thousands of years the last sea dried out in the 1500s. The Colorado River, once flowing into the basin, had assumed its current course to the southeast. Nature had chosen its path.

Human's rarely get along with nature.

The temperature here is perfect for growing crops all year. But crops need water. The Colorado was the only water around. Luckily, by the early 1900s human engineering and real-estate speculation was able to conquer nature.

A state sponsored developer began an irrigation project. Canals and drainage systems were constructed to bring water from the river to the new farm properties of the area, promising a steady supply of fresh water to grow.

In 1905, one of these canals burst, and water started flooding back into the basin for the next two years.

The Salton Sea filling up wasn’t a disaster. It was a big fuck up by the California Development Company, submerging a few scattered settlements, but it ended up creating a whole new ecosystem. Fish found their way into the sea from the river, and birds and other small animals flocked to the new wetland in the middle of the desert. Where we sent water we made a new world.

In the 1940s as California boomed, a resort economy began to develop as the Sea became a destination for relaxing, boating, birdwatching and sports fishing. Settlers grew wealthier, opening businesses to cater to the growing tourism from Los Angeles and Palm Springs. In this Sea they found their Western Prophecy.

The farms of the area were some of the most productive in the country, but their inefficient water consumption meant that runoff was common. Excess irrigation water carried fertilizer, pesticides and other toxic byproducts into the Sea. At the same time, the salt embedded in the basin’s sea bed continued to leech into the water leading to ever-growing salinity. Both of these problems were compounded by the lack of a natural outflow from the Sea. The stagnant water continued to grow in salinity and toxicity, while simultaneously beginning to dry up.

By the 1960s scientists were ringing the alarm. The oasis in the desert was on the precipice of a major disaster. And by then there was little that could be done to stop it.

It started with the fish.

Large scale die-offs brought hundreds of fish to the surface of the Sea and it’s receding banks. The birds which flocked to the Sea for the fresh water and abundant fish found neither there anymore. They left.

The rotting fish and toxic water meant that no tourists wanted to visit. They couldn’t swim, and they couldn’t even stand on the beach due to the foul smell. As the tourists left, so did most of the locals, abandoning their homes and trailers to vandals and decay. With the only jobs left being farm labour, the area fell into an economic despair from which it hasn’t recovered. But there are new signs of life.

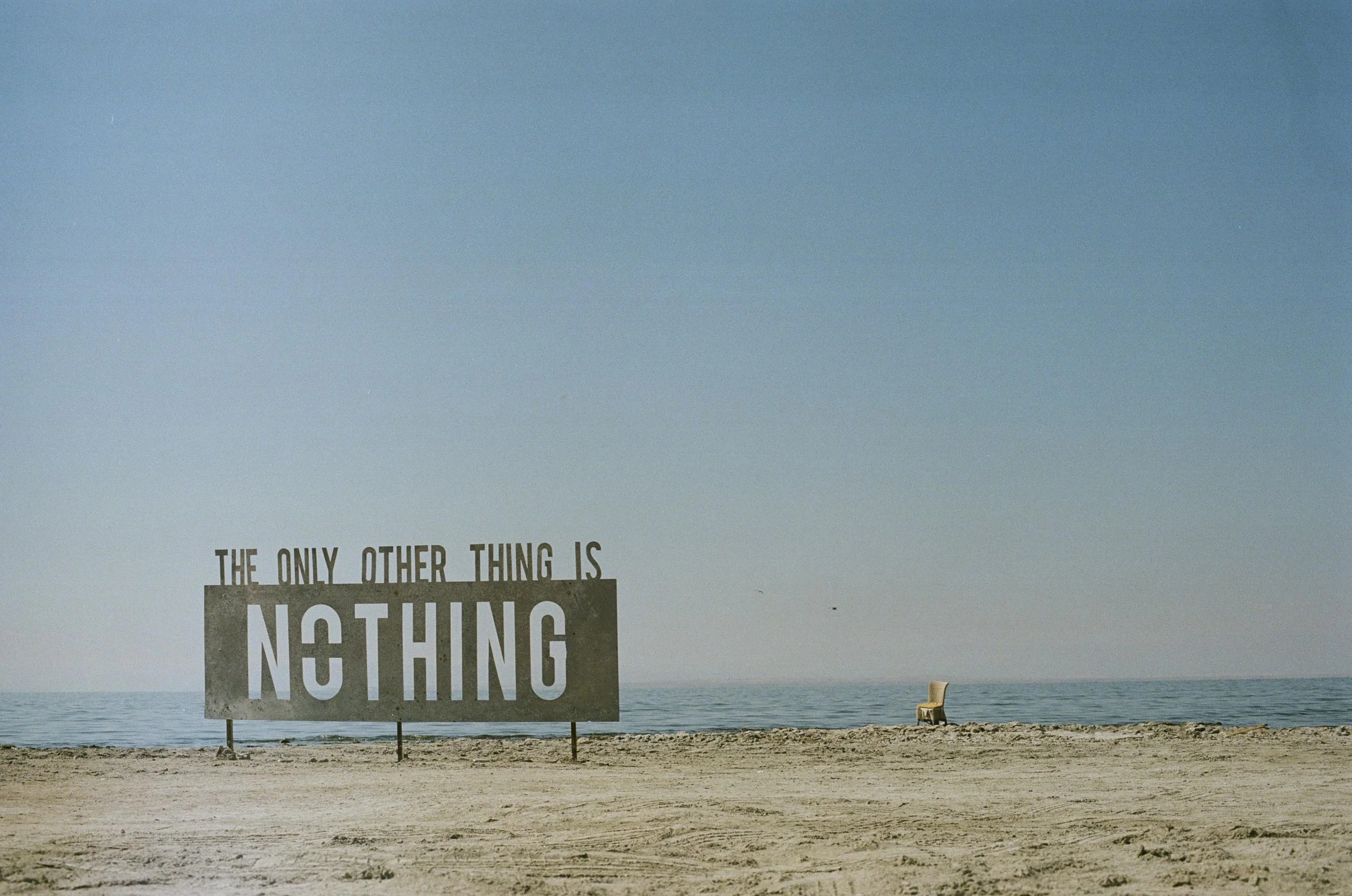

On almost every property in Bombay Beach there is some kind of installation art. Certain pieces riff on the town’s reality to make a statement. Others ignore their surroundings for a standalone mission. A few of them light up at night, while others are made to capture the sun art a precise time of day.

This creative renaissance is a mixture of visiting artists passing through with an idea, and inventive locals personalizing home. The town’s beach has become the mecca of this new art scene, with dozens of pieces rising from the sand and sunken in the shallow water.

We arrived after dark in Bombay Beach, later than we’d wanted. With only a few weak street lamps, most of the town lay hidden in the darkness of the hot, putrid, still night.

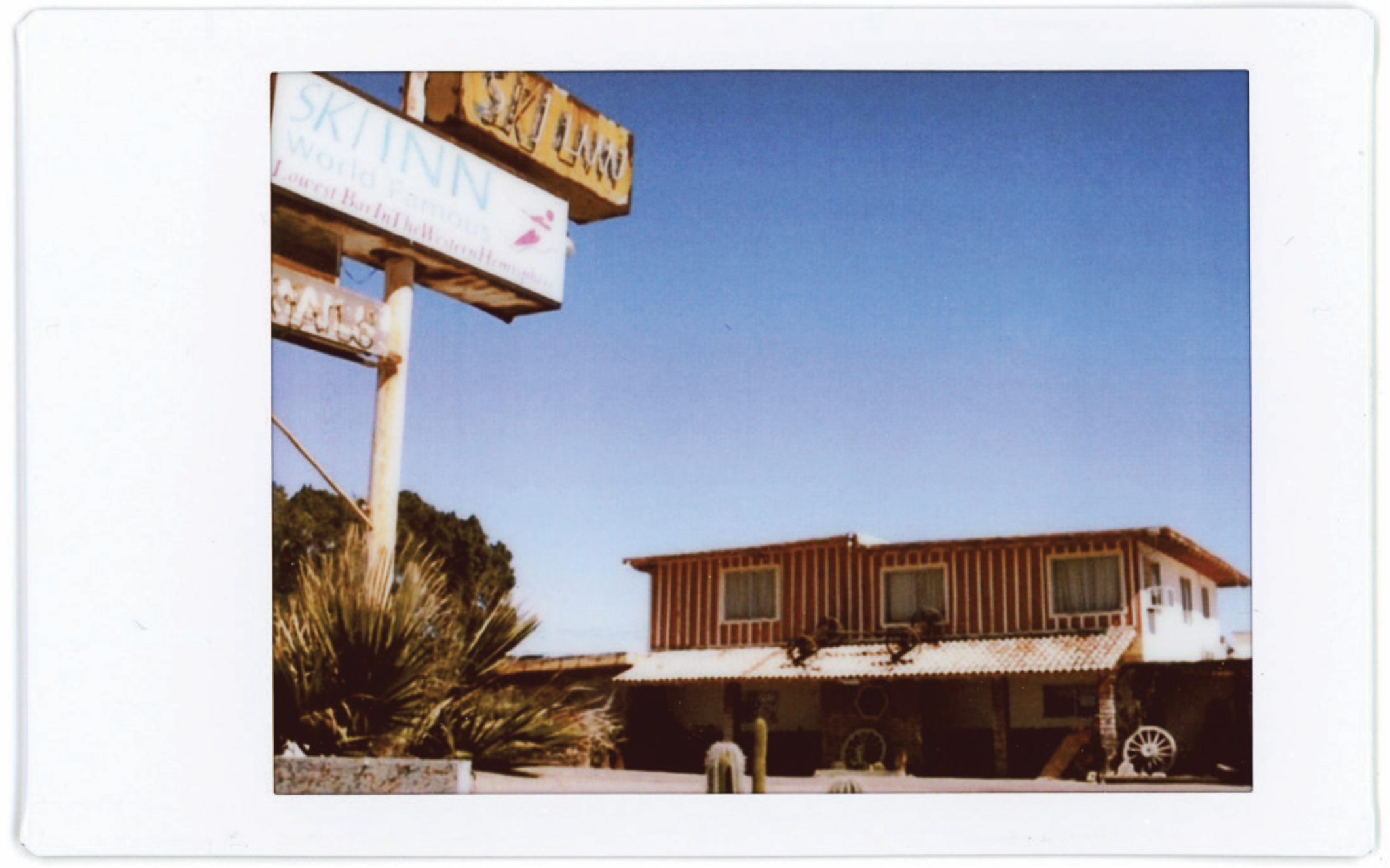

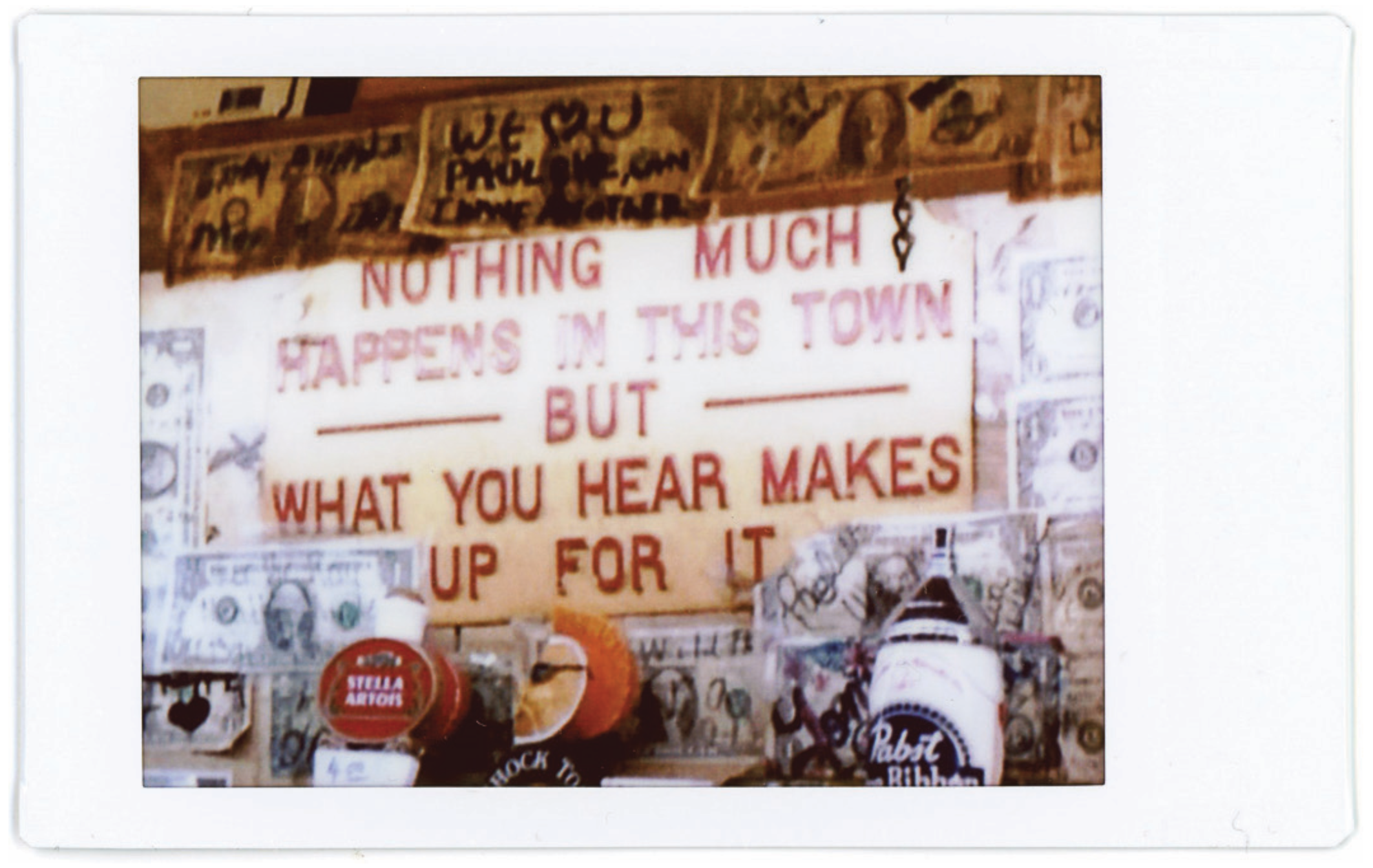

The only restaurant in Bombay Beach is the amusingly named Ski Inn. It is open until 2AM most nights, serving up drinks and pub food in a large dining room lined with photos, memorabilia and a lot of taped up dollar bills. It is the hub of Bombay Beach, and we went there hungry from the full days drive. What happened next was surreal.

We entered the bar to yells from about eight drunk locals. Over the loud classic rock playing on the stereo they shouted that this was a participation mandatory bar. We humoured them, yelling and cheering but alarmed at what we’d walked into. But this was the adventure we chose. An older woman runs the bar. We headed over to her.

“My friends and I are super hungry.” I announced to her. I’m not usually that forward. Maybe it was because I was on edge. Or because I was super hungry. Both probably.

She looked caught off guard for a moment, but calmly told us the kitchen had been closed all day because the restaurant had hosted a memorial. She brushed off our apologies with a smile and offered to bring us the leftover snacks from the service.

The rest of the restaurant was empty. I picked a table halfway to the bathrooms, not too far as to seem anti-social. True to her word, she brought a selection of finger foods from the service. A charcuterie spread, chips and veggies with dip. Brave and confident in my stomach’s abilities, I dug into all the plates while my friends stuck to picking certain pieces out.

It felt a bit weird to be eating food with these connotations, but I assumed it was basic survival. The next closest restaurant of any kind was over 45 minutes away, and the car didn’t have enough gas to make it there anyways. We settled into our round of drinks and “dinner",” bewildered at what we had stumbled into. A woman from the group made her way over to the memorial table, at the far wall behind us. I hadn’t noticed this table before she walked over. She broke down into tears, sobbing alone for a moment or two before a man from the group came over and embraced her.

Even though it didn’t seem like they cared - even noticed - that we were there, it still felt like we were intruding. Something clicked.

In all my personal focus on the Western Prophecy I rarely regarded the human experience here at an individual level. Maybe it was due to the mythos this land held for me. The feeling that it was only real for the week or two I’d pass through it every year. Maybe it was my focus on events of the past and how they created the inanimate world of my surroundings. Maybe it was because out in the desert you rarely see a soul.

Somehow the idea that there were real people here going through real trials and tribulations, grieving and celebrating, living and dying, didn’t become clear until I watched this woman sob in front of the memorial table at the Ski Inn.

The farmers escaping the dust bowl, the motel owners on Route 66, the fishing guides of the Salton Sea; They all had full lives beyond what I described in this book, beyond their legacies still visible at the side of the road. I bet when they were alive, they weren’t focues on leaving behind a neon sign when they left. They were preoccupied with their reality. In this place of very few people, this reality simply had enough of an impact that the remains were preserved.

Whatever this land promises you, whatever dreams are held in your Western Prophecy, it is all ephemeral. You live and you die.

I just hope that when I do, there will be something that can be left behind in a desert somewhere. And that I’ll have at least one person there ready to cry for me, and one more ready to get drunk for me.